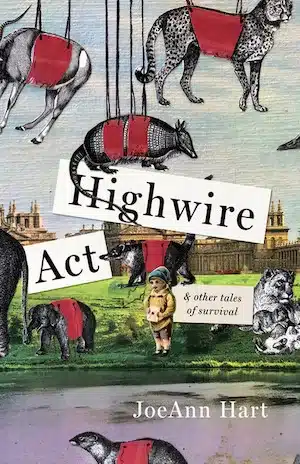

JoeAnn Hart, long-time contributor to EcoLit Books, is the author of three novels (including Float) and a forthcoming short story collection from Black Lawrence Press: Highwire Act & Other Tales of Survival.

This collection, the winner of the 2022 Hudson Prize, includes stories that have been published by a number of literary journals, including Prairie Schooner, The Hopper, The Sonora Review, and the anthologies Among Animals 2 and Among Animals 3. When taken as a whole, this collection reflects the world back to us in ways both familiar and foreign and utterly unforgettable.

JoeAnn was kind enough to answer a few of my questions…

A number of your stories are about grief for a dying planet. And, to borrow from Kübler-Ross, the characters appear to be caught somewhere between the stages of Denial and Acceptance. How do you as a writer navigate between these stages, if at all?

When writing climate fiction, it’s very hard not to turn all dystopian. To accept what is happening to the planet risks falling into despair, but to deny what is going will prevent taking any action. Every story in Highwire Act is a balance of these elements, and every character has their own way of coping, or not. As a writer, the trick is to have hope. It is not enough to describe what we’ve lost, we must also be able to imagine joy. As Oliver Sacks once said, “The most we can do is to write — intelligently, creatively, evocatively — about what it is like living in the world at this time.”

In “Reef of Plagues,” you write, “Years now, the coral has been fading like a shadow on the water, but no help came until the tourists themselves became endangered. The scientists do not discuss what will happen if the reef dies altogether, but we can read the signs. We know our fate.” And we see the disappointed tourists through the eyes of the locals, but we also witness talk of gods and goddesses. I’m curious what role gods and goddesses have in a world in crisis? Do they give the locals hope? Should they give us hope?

“Reef Of Plagues” was a commissioned story, so I had parameters to follow. The story had to be about the oceans, and it had to loosely follow The Odyssey. Hence the gods and goddesses. On a secular level, they are a stand-in for wonder, which might egg us on to actually try to save the world. They also represent our reliance on powers outside of ourselves to save us. In this story, a goddess in the form of a babysitter leaves a fossil-fueled vessel which is oblivious to the damage it is causing to the seas, and joins those mortals who are at least trying to help. When all else fails, we might have to call upon a goddess to get the job done.

From a craft perspective, the stories in this collection feature myriad styles and points of view — from the first-person plural in “Reef of Plagues” to second-person in “When You Are Done Being Happy” to nearly all dialogue in “Thirteen Minutes.” Did you begin each story with these elements of craft in mind, or did they evolve as you got into each story?

When writing short fiction, I almost always start with an image in my head, and through some process of which I am only vaguely aware of, the image dictates the style and determines the voice. The tools and material, such as plot, perspective, narrator, and tense, emerge from that all-important voice. I discover the story itself as I write, with one eye on interesting scientific facts because research is part of my process, so in this way, the journey through the material becomes the story. I also find that trying out different styles and perspectives challenges the brain, and if you keep challenges new, you can solve problems a new way.

Both humans and nonhumans (from mammals to dying coral reefs) suffer in many of these stories. How is their suffering similar and how is it different, and how do you feel they connect and inform one another?

As the planet continues to warm, all living things will suffer. We are all suffering now. The key issues in many of the stories is how do we as the apex species respond to it. In “It Won’t Be Long Now,” a woman equates the suffering of a stranded seal with her own, and believes it gives them a special bond. This does not end well. Animals don’t want our sympathy, they want us to stop torturing them with our technology. The same is true of humans in “Reef of Plagues.” Island and poor coastal communities around the world, who produce hardly any carbon emissions themselves, will suffer the most from global warming. They don’t want advice from the carbon-heavy countries on how they should deal with rising and warming waters, they want us to change our behavior and make it stop.

Survival, of course, is a theme in this collection — physical as well as emotional. How did these stories come together as a whole — did you write each one with this collection in mind, or did the theme emerge gradually?

The stories in Highwire Act were written over a period of almost twenty years. The earliest story, “Woodbine & Asters,” was published in Prairie Schooner in 2006, meaning I probably wrote it in 2004 or before. In all that time, I wasn’t conscious of writing about survival over and over again, but since I often explore how humans interact with their environment, it was a theme that developed on its own. It wasn’t until I was choosing stories to shape a collection for contests that I saw the pattern, and purposely selected those that spoke to survival in some way. So even though the collection has wildly different stories and styles, it has a certain unity, which probably attributed to its winning the Hudson Prize.

You end the collection with the painfully beautiful “When You Are Done Being Happy.” You write, “When you are done being happy, decide that life is not a list of events to be experienced but a set of questions to be answered, and not the sort of question you used to ask, like, is the eye really the only bloodless organ? You must ask yourself the big questions.” What questions are you asking now as a writer, as a person?

I am always asking the question “What are we doing here?” This isn’t just about how we should live a moral life, which falls under religious instruction, but how do we live on the Earth without harming other living things, including ourselves. It’s not about finding one’s personal journey, but wondering out loud if humans as a species even have a purpose. If we were to be plucked off the planet right now, not only wouldn’t it miss us, it would heal. What do we make of that?

What would you like readers to take away from these stories?

I can’t offer solutions or answers to the mess we find ourselves in, but I do hope that I raise questions that might inspire action. It’s why I ended the collection with “When You Are Done Being Happy,” which directly addresses that. We have to figure out how to survive, and in order to do that we must be willing to commit to the survival of all living things, because we’re all interconnected in the fragile biosphere.

What story was most challenging to write and why?

Definitely “Reef of Plagues.” When I was invited to the International Literature Festival in Berlin to present my novel Float, a dark comedy about plastics in the ocean, I was also asked to write a short story for their program ”Reading the Currents, Stories from the 21st Century Sea.” I had strict guidelines about subject, length, and deadline. Usually I’ll start a short story when the spirit moves me, and I might diddle with it for a few years on and off before I consider it done. So there was a lot of pressure to write this story, but it was good to have my skills challenged. It was well-received at the festival, where it was translated into German and read by an actor to the Berlin audience, followed by a marine biologist to discuss the science in the story, all of which in a language I barely understood. As I was writing the story, I was also trying to learn some German before I got there, which was a challenge of its own.

What story was most personal? And why?

All the stories have some deep connection, but “Infant Kettery” is probably the most personal. When I’m writing a novel, I’ll sometimes jump ahead and write a short story with the characters so I can learn more about them. These often become chapters. I did this a few times with my novel Float, as well as with my forthcoming novel, Arroyo Circle, from which sprung “Infant Kettery.” I began writing Arroyo Circle when my brother died of cirrochis a few years ago. Although he had a roof over his head at the time, he had been homeless for much of his life. To help process my grief I tried to imagine what that was like for him, living and sleeping in public spaces, like the cemetery where this story is set. As my character, Les, wakes up, he reflects on a dying cow, then wonders about the infant whose grave he’s leaning against. He can’t do anything about the deaths except to be present. And that, I hope, is enough.

Highwire Act & Other Tales of Survival

Black Lawrence Press

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island. He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).