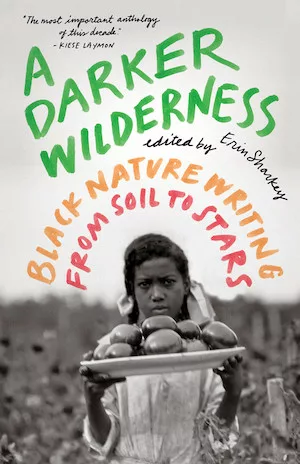

New this year from Milkweed Editions is a must-read essay collection of powerful Black nature writing. Originated and edited by Erin Sharkey, A Darker Wilderness: Black Nature Writing from Soil to Stars is a stunning and needed anthology. These essays by eleven contemporary writers address the presence of Black people and their contributions not only to the literary field of nature writing, but to America’s relationship with nature itself—which is complicated at best. Sean Hill pinpoints the crux of the problem in his essay “This Land is My Land”: “This land was stolen, as were my ancestors.”

In her introduction, Sharkey establishes nature writing’s historical connection to colonization. The field of nature writing, she writes, is a result of “the work of empire, conquering and cataloguing.” This is partly why the essays in this collection interact with archival objects, including photos, artworks, documents, family artifacts and more. The process of creating this book helped connect these historical photos and objects “to contemporary Black thinkers across time and, in turn, rewrites the record.”

Rewriting the record is essential when America’s most beloved natural features—like those preserved in the National Park System—have been historically white spaces. As Naima Penniman opens her essay “Concentric Memory: Re-membering Our Way into the Future,” “It’s no wonder the forest can be a terrifying place for Black folks. I don’t even have to tell you.” In the essay “An Aspect of Freedom,” Ama Codjoe reflects on the murder of Ahmaud Arbery—who was killed for simply being outside as a Black man—and its haunting effect on her: “I notice the Southern magnolia blossoms, in various stages of bloom and decay, and feel the target on my back.”

While the pages of A Darker Wilderness address and grapple with life under and alongside racist systems—including the fact that enjoying freedom in nature is often only truly accessible to the privileged—they also honor nature as a crucial companion and provider throughout the African-American experience. In Carolyn Finney’s foreword “Memory Divine,” Finney reflects on how her parents, like many Black families throughout the twentieth century, nurtured a far more intimate relationship with their land than the white family that legally owned it. And Penniman’s essay explores how, for Haitian revolutionary leader François Makandal and anyone else resisting slavery throughout America, “the forest was an ally in this quest for self-determination.”

Some of the essays are in dialogue with specific historical thinkers. These include Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s introspective piece “Water and Stone: A Ceremony for Audre Lorde in Three Parts,” which ponders the idea of Lorde as a nature writer, and Sharkey’s “An Urban Farmer’s Almanac: A Twenty-First-Century Reflection on Benjamin Banneker’s Almanacs and Other Astronomical Phenomena,” which considers eighteenth-century naturalist Benjamin Banneker and applications of his work in today’s world.

Other essays range from personal narratives to historical research. In “A Family Vacation,” Glynn Pogue reflects on spending the Fourth of July in 2020—a particularly charged and unsettling time after the murder of George Floyd during the first months of the pandemic—on vacation with her family. She beautifully weaves in a veritable history of Black vacation culture and an exploration of vacations in nature as healing experiences. Lauret Savoy’s essay “Confronting the Names on this Land” is a fascinating lesson on the names given to land features in the United States. In a captivating discussion centered around a rock in the Grand Canyon region that was assigned a slur-name in a 1909 expedition, Savoy demonstrates that naming “is not innocent, passive, or neutral.”

Ronald L. Greer II’s essay “Magic Alley” invites readers to re-consider which environments can constitute nature. Greer writes about growing up playing in “a drab, drug-infested, gravel-paved alley in the heart of Detroit,” with his grandfather’s vegetable garden in the middle of it all. Through Greer’s child-self’s perspective, the reader understands the sacred power and meaning that Greer’s environment took on for him. “[My] imagination created fierce and ferocious creatures,” he writes. Seemingly unpoetic elements like hypodermic needles became “deadly little dandelions with venomous, hidden stingers, waiting to poison their next prey.”

Nature is brilliantly defined and re-defined in A Darker Wilderness. Codjoe defines nature as “anything that gives nourishment and everything that breathes.” Sharkey writes that nature “isn’t bad or good. Nature is a relationship, a big map of interconnectedness, of needs met, bodies transformed.” Hill defines sublimity instead: “that awe-inspiring element of being attentive to, being aware of, existing in the world.” And Michael Kleber-Diggs, in his heartrending essay “There Was a Tremendous Softness” about growing up after the tragic killing of his father, uses nature in a simple, affecting analogy: “grief : people :: water : rock.”

A Darker Wilderness lays bare and interrogates the dark histories and difficult experiences shared by Black people in America. It also celebrates and converses with the wisdom of what Penniman calls “our devoted babysitter Mama Nature.” Not only does this project successfully help “rewrite the record” of the past as Sharkey intended, but its sincere, meditative prose is sure to inspire readers to find deeper connections to our authentic selves in this country today—and to consider the responsibility we all have to shape the future from here.

In their gorgeous essay “Here’s How I Let Them Come Close,” katie robinson writes:

I think we are nature. … I am built and natural, I am a climate emergency, rearranging myself and letting myself die. I am the sky and the aberration, the breathing moving body and the breathing rooted one, the one approaching and the one being approached. When I fear, I know I am touching something, I know I am alive. We are what we think we are, we are what we never considered we could be, and we are a mystery, all at once.

Lillie Gardner is a writer based in St. Paul, Minnesota. Her work has been published in Quail Bell Magazine, Delmarva Review, Long River Review and more. She’s also an essays reader for Hippocampus Magazine and a contributor at Feminist Book Club.