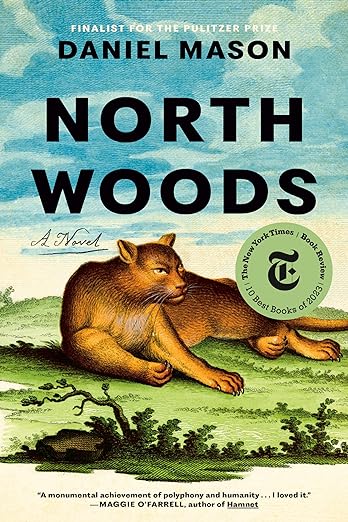

Random House, 2023

“Shivers of lust passed through his elytra as he found her scent grow stronger,” and there we are, in the head of an Elm Bark beetle, one of many POVs in the thoroughly enchanting novel North Woods by Daniel Mason. The beetle had been deposited in this wooded piece of land in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts by a human, left to spread the devasting effects of Dutch Elm disease. In other sections, the narrative is revealed through the likes of a stuffed catamount, doctor’s notes, true crime columns, academic papers, and prison pen-pals – what could go wrong? Just about everything it seems, as we experience the American story through the lens of this property. Before the 1700s, the forest had been a healthy Eden, lightly inhabited by Native Americans who extracted just enough to sustain themselves, and no more. Then one by one, British colonizers appeared, elbowing tribes out of the way with either violence or lies, or both, taking possession of the land with the intent to build wealth, extracting more than was needed to survive, then selling the surplus. North Woods is the story of American expansion and capitalism, where the natural resources of the colonized lands were squandered for individual profit. It is a familiar tale, but Mason presents it with an abiding love and respect for the natural world, and not a little humor. When an early resident sniffs a vile vial of potion, the stench is so strong that “there was a thump from the parrot cage.”

The property’s storyline begins with a runaway colonial couple, cast not out of Eden but into it, and are the first Europeans to occupy the woods. Every Eden must have its apple, and one arrives as a single seed in the stomach of a man left to rot, and from his carcass a fortune grows, enabling an orchardist to build the first real house on the land. “When I bit into it, I had the sense of tasting not only with my tongue, but deep within my palate, a scent more than a flavour, as light as lemon blossoms, before a second wave came spreading through like syrup.” More’s the pity when his spinster daughters manage the land when he’s gone, and the dominant sister clears the orchard to raise sheep for the wool market. “In the savaged field, the fallen trees were rendered of their bark left pale and moist and animal.”

This daughter is pretty clever with an ax, but there is still an apple tree or two left a century or so later, when a new owner, an artist, tastes the apple and exclaims “Henceforth, it shall be forbidden to call anything else an apple.” There is a touching epistolary section between the artist and his close friend, reminiscent of the letters between Nathanial Hawthorne and Melville when they summered in the Berkshires. The artist is seduced by the natural world he paints, but he is not blind to its dangers. “Woods, from the Old English wode — also meaning ‘mad’” And mad these woods are, as one inhabitant or another are driven to insanity or strange acts of violence. By the end of the artist’s life, nature begins to reassert itself, and the house is filled with “Strips of bark and withered clumps of fungus. Bones of animals. Piles of porcupine quills. Dried grey tufts of goldenrod, cracked pods of milkweed, fern fronds, jars with insect specimens.”

This is not the story of a home lovingly handed down through the generations. Few owners are related because these are not people who prosper long, and often die without progeny. An Eden lost through a lack of respect. One owner wanted to make his fortune by turning the house into a “high-end lodge, with quality people only.” It took him two months to clear out “the useless, tangled apples” for the croquet court. But how to get rid of the ghosts? Enter the psychic, who announces that “it is a well-accepted fact that, even in the firmest substances, the atoms do not touch, and there is ample space for other worlds.” Oh, is there. The past residents can’t seem to let go of the old place. When a true crime columnist comes to investigate suspicious events, he writes: “Know the land and know the killer. Man’s a product of his environment, and that’s true for the upright and the sickos alike.” In contemporary time, a naturalist comes to study the woods. “No sooner had she learned her trees than she began to understand the degree by which the trees were changing.” The story of this precious piece of woods extends a bit into the future, and it’s just what you’d expect when humans put their own wants over the care of the very land they inhabit.

JoeAnn Hart writes about the pervasive and widespread effects of the climate crisis on the natural world and the human psyche. Her most recent book, Arroyo Circle, a story of reclamation in a time of loss, was released by Green Writers Press in 2024. Her other books include the prize-winning environmental and animal fiction collection Highwire Act & Other Tales of Survival, the crime memoir Stamford ’76: A True Story of Murder, Corruption, Race, and Feminism in the 1970s, as well as Float, a dark comedy about plastics in the ocean published by Ashland Creek Press, and Addled, a social satire. She is a regular reviewer of climate and animal fiction at EcoLit Books.