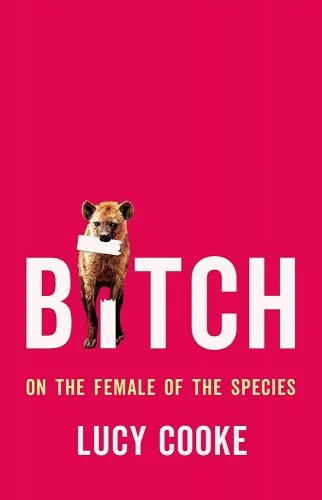

As a zoology student, Lucy Cooke was taught that the females of the species are exploited, weak, and passive. As a human animal, Cooke begged to differ. In Bitch: On the Female of the Species, she challenges this sexist mythology across species, from birds to primates to whales, showing that females can be just as sexually promiscuous, competitive, and formidable as males.

Beginning with the argument that Darwin’s theories of the passivity of the female species was influenced by the Victorian era’s “social prejudice,” Cooke goes on to show evidence that female animals are, in fact, anything but, based on the research of contemporary scientists (many, but not all, female). She notes the longtime gender bias in research and even in scientific language, showing that science is not immune to cultural influences. “It has taken the biological sciences a long time to face these failings,” she writes. “Feminism has played a key part.”

In a response to Darwin’s “forcing the female of the species into an ill-fitting chastity belt,” Bitch offers a much-needed, eye-opening look at an animal world that reveals behaviors and perspectives long overlooked: from dominant female activity to non-human menopause.

Bitch will appeal to anyone interested in animal life, and its focus on the diverse sexual development, sexual characteristics, sex lives, and behaviors of non-human animals makes it a fascinating read, not only for the science but for Cooke’s witty anthropomorphism and her stories from the field. In a chapter on choosing mates, Cooke writes, “Female animals have rather a lot to answer for,” noting the extravagance of the male greater sage grouse’s mating dance (the males inflate the esophagus “by gulping down mouthfuls of air to create a large wobbly white-feathered throat balloon, which when fully swollen briefly exposes two bulbous patches of olive-green skin that pop forth from their feathers like a pair of nippleless shop-dummy breasts”), the male proboscis monkey’s “long and pendulous nose,” and the stalk-eyed fly’s “unwieldy horizontal eye-stalks.” In another chapter, Cooke writes, “It’s not unusual for a lioness to be spotted creeping away from her napping partner in order to engage in saucy trysts with other males.”

Cooke’s research challenges myriad biological myths, such as the female monogamy of certain species; many birds, for example, are socially monogamous but not sexually monogamous: “We now know that 90 per cent of all female birds routinely copulate with multiple males and, as a result, a single clutch of eggs can have many fathers.”

While Cooke covers topics from philandering females (when ovulating, a wild chimpanzee “might solicit every male in her community and have sex 30-50 times a day”) to sexual cannibalism (“the female spider’s penchant for rolling dinner and date into one”), Bitch isn’t only about sex. Take the complexities of animal parenthood: Female owl monkeys nurse their young every few hours—then leave the other 90 percent of caregiving to the fathers. In almost two-thirds of fish species, males do the nursing. For many working-mom baboons, who spend 70 percent of each day “‘making a living’—foraging, walking, avoiding predation” and raising her child, infant mortality is 30-50 percent in the baby’s first year.

And when it comes to conflict and culture in the wild, males aren’t the most violent or ruthless of the species. While on most nature shows you’ll see males fighting over females, Cooke’s research shows this is not the rule: For example, female topi and western lowland gorillas physically fight over males, and female songbirds use their songs to compete with other females. And those adorable meerkats? “Meerkat society is predicated on ruthless reproductive competition between closely related females who, when pregnant, will readily kill and eat each other’s pups.”

Cooke’s engaging writing style makes Bitch’s science accessible for all readers, and the research is especially interesting as we face a sixth mass extinction. In a chapter that features females who reproduce without males, Cooke writes, “females that can fall back on the ancient art of cloning might just be what’s needed to help species weather tough times.”

And as the book highlights the diversity of myriad non-human species, it also calls for a diversity of humans in science. As Cooke notes, the rules of evolutionary biology were developed by “white, upper-class men from Western post-industrial societies,” and fresh voices and perspectives in science have made new research—and this book—possible. Good science depends upon eliminating biases, and for this to happen, Cooke notes, “We also need a diversity in the people producing science.”

Cooke’s own hope for her book is, as she writes, “to paint a fresh, diverse portrait of the female animal, and to try to understand what, if anything, these revelations can inform us about our own species.” Much of the work Cooke shows in Bitch about the powerful females of myriad species comes from women scientists who’ve looked beyond what’s been done before, through a patriarchal lens. And while Bitch’s portrait of the female animal does inform our own species, better yet, it goes beyond by celebrating extraordinary non-human females in their own right.

Midge Raymond is a co-founder of Ashland Creek Press. She is the author of the novels Floreana and My Last Continent, the award-winning short story collection Forgetting English, and, with John Yunker, the suspense novel Devils Island.