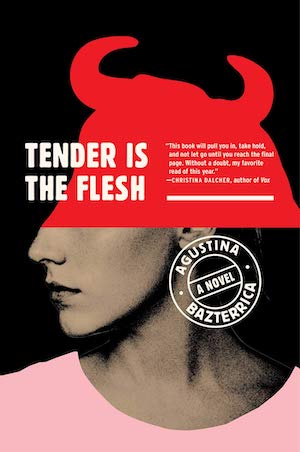

In Tender is the Flesh, Agustina Bazterrica expertly crafts a horrifying reality that feels too contemporary to be the future. A virus has decimated the world’s animal population. Societies around the globe, rather than shifting to vegetarianism, continue to demand meat at alarming costs. Governments have legalized cannibalism (which has the added benefits of curbing overpopulation and reducing poverty), and factory farms have reopened for the breeding, slaughter, and processing of humans.

The story centers around Marcos Tejo, a respected processing plant worker who is emotionally broken after his baby’s death. Marcos lives his life on autopilot, doing what he needs to do to survive one day at a time. His distraught wife lives at her mother’s, his sister is a social-climbing burden, and his father is succumbing to dementia in a nursing home. Marcos and his family members are reacting in their own ways to “the Transition”—the recent period of this dystopian world in which cannibalism became the norm.

Throughout the novel, the reader follows Marcos on his “meat runs.” Breeding centers, processing plants, and butcher shops exist for the slaughter and distribution of human meat. High-quality “heads” are hunted and eaten at luxury game reserves for the rich. (Strong males and pregnant females are most in demand.) And upper-class kitchens have “cold rooms” where families keep living heads and cut pieces from them to serve for dinner. Think: a platter of filleted human arm surrounded by lettuce and radishes.

Outwardly strong and unaffected, Marcos internally flails in cognitive dissonance. He supplies human skins to the tannery, yet he wants the tannery to disappear. He oversees the slaughter of humans, yet he doesn’t eat meat. He is acutely aware that “no one who’s in their right mind would be happy to do this job,” yet he rationalizes his work with his need to support his father. When Marcos is given a female to keep in his barn for slaughter, he is forced to confront his broiling internal conflict with action. The stakes are high: kill or be killed.

The novel opens with a quote from philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “What we see never lies in what we say.” Marcos is more interested in the saying than the seeing; he parses through words to divide them into those that reveal reality and those that cover it up. He experiences people more through their language than through their appearances or roles. Marcos’s sister’s words “accumulate, one on top of the other, like folders piled on folders inside folders.” A stunner at the processing plant has “words that don’t have sharp edges.” The butcher uses “frigid, stabbing words.” After their baby died, Marcos’s wife’s “words became black holes, they began to disappear into themselves.”

Other times, words mask rather than define reality. “[Marcos’s] brain warns him that there are words that cover up the world,” reads the novel’s first page. “There are words that are convenient, hygienic. Legal.” Humans bred for meat are referred to as “heads.” The heads’ hands and feet are renamed “the Upper and Lower Extremities.” Killing is called “processing.” Far from being an imagined future language of the oppressed, the language in Marcos’s world mirrors (and borrows) our real-world language about animals: a body part is a “product,” a pig is “pork,” an animal is an “it,” and killing is still “processing.”

While Bazterrica’s parallels to animal factory farming are achingly clear, most powerful is her demonstration of how meat connects to all areas of society. In Marcos’s world, legalized cannibalism shapes the disturbing organization of nursing homes, feeds on racism, wipes out immigrant populations, depends on class distinctions, and fuels misogyny through permitting unspeakable violence against women and creating an especially harrowing sex trafficking trade.

“After all, since the world began, we’ve been eating each other,” says the owner of a game reserve where celebrities are hunted in exchange for debt forgiveness. “If not symbolically, then we’ve been literally gorging on each other.”

If you can stomach the content, Tender is the Flesh is a captivating read that explores the lengths we’ll go to stay alive and the horrors we’ll accept to conform, making the bone-chilling case throughout every scene that inequality, literally, is what feeds us.

Lillie Gardner is a writer based in St. Paul, Minnesota. Her work has been published in Quail Bell Magazine, Delmarva Review, Long River Review and more. She’s also an essays reader for Hippocampus Magazine and a contributor at Feminist Book Club.