It is difficult to separate Moby-Dick, the book, from Moby-Dick, the whale.

Both are epic in scale, and both have been met with wildly different perceptions and interpretations.

You only need to browse Amazon reviews to get a taste.

I’ve now read this book twice, and I can’t say that the second time around was any easier than the first, though the second time was a different experience.

The first time I read the book, I was awed by the construction, the different styles of writing, and the numerous, mind-numbing asides that Ishmael takes with the reader.

On my second time through, I found myself thinking again and again about just how sad it all was.

Many years have passed between my first reading and my second and, in those years, I’ve come a very long way in how I view the animals we share this planet with.

Where once I was content to view the whale as an adversary or antagonist, I now see a creature simply trying to defend himself.

I also see a human species hell-bent on extracting every last living creature from the sea.

And, worse, spinning the entire endeavor into some high-seas adventure.

I can’t say with any degree of certainty that Herman Melville felt sad for the whales — or guilty for his role while he worked on a whaling ship. But several times during the novel I got the feeling he was struggling with this issue. On occasion, Ishmael imagined the oceans from the whale’s perspective, and was often amazed by the great intelligence, empathy, and bravery the species displayed through their actions. Melville writes:

The more I consider this mighty tail, the more do I deplore my inability to express it. At times there are gestures in it, which, though they would well grace the hand of man, remain wholly inexplicable. In an extensive herd, so remarkable, occasionally, are these mystic gestures, that I have heard hunters who have declared them akin to Free-Mason signs and symbols; that the whale, indeed, by these methods intelligently conversed with the world. Nor are there wanting other motions of the whale in his general body, full of strangeness, and unaccountable to his most experienced assailant. Dissect him how I may, then, I but go skin deep. I know him not, and never will. But if I know not even the tail of this whale, how understand his head? much more, how comprehend his face, when face he has none? Thou shalt see my back parts, my tail, he seems to say, but my face shall not be seen. But I cannot completely make out his back parts; and hint what he will about his face, I say again he has no face.

In one passage in particular he calls out not only whale hunters specifically but carnivores in general:

It is not, perhaps, entirely because the whale is so excessively unctuous that landsmen seem to regard the eating of him with abhorrence; that appears to result, in some way, from the consideration before mentioned: i.e. that a man should eat a newly murdered thing of the sea, and eat it too by its own light. But no doubt the first man that ever murdered an ox was regarded as a murderer; perhaps he was hung; and if he had been put on his trial by oxen, he certainly would have been; and he certainly deserved it if any murderer does. Go to the meat-market of a Saturday night and see the crowds of live bipeds staring up at the long rows of dead quadrupeds. Does not that sight take a tooth out of the cannibal’s jaw? Cannibals? who is not a cannibal? I tell you it will be more tolerable for the Fejee that salted down a lean missionary in his cellar against a coming famine; it will be more tolerable for that provident Fejee, I say, in the day of judgment, than for thee, civilized and enlightened gourmand, who nailest geese to the ground and feastest on their bloated livers in thy pate-de-foie-gras.

But Stubb, he eats the whale by its own light, does he? and that is adding insult to injury, is it? Look at your knife-handle, there, my civilized and enlightened gourmand, dining off that roast beef, what is that handle made of?—what but the bones of the brother of the very ox you are eating? And what do you pick your teeth with, after devouring that fat goose? With a feather of the same fowl. And with what quill did the Secretary of the Society for the Suppression of Cruelty of Ganders formally indite his circulars? It is only within the last month or two that the society passed a resolution to patronize nothing but steel pens.

I suspect, based on Melville’s earlier writings, that he initially set out to write another epic adventure — the type of book that always sells — but at some point found himself writing something quite different, less black and white, more ambitious.

Now, is this book eco-literature?

Absolutely.

While you could argue that the book glorifies whaling, I get the sense — certainly the second time around — that Melville was playing more the role of the documentary filmmaker, displaying the gruesomeness of it all. I’m not sure he was trying to turn people against whaling — for the industry was already seeing its days numbered at that point in history — but I think he was deeply conflicted about the industry and America’s role in leading it.

I think Ahab holds the clue to the novel, a man obsessed with the “one that got away.”

And this obsession is with our culture still.

When I finished reading the book I noticed that the Spielberg film Jaws was on the television. And in that movie we see the very same dynamic at work. This demonization of nature, this never-ending need to control that which cannot be controlled, and the irrepressible need for humans to create monsters where monsters do not exist.

This text from Ahab’s perspective:

God help thee, old man, thy thoughts have created a creature in thee; and he whose intense thinking thus makes him a Prometheus; a vulture feeds upon that heart for ever; that vulture the very creature he creates.

From sharks to whales to seals and, on land, to wolves and bears and even deer –the pattern repeats.

I believe eco-literature has an important role to play in making this pattern apparent to people so that we may finally one day break it.

As an aside, for years I believed that Moby-Dick received bad reviews simply because the public wasn’t ready for such a “modern” work. But I recently read that London readers first experienced a book that was missing entire sections, including the epilogue.

At any rate, the book is a fascinating and challenging read for both its glimpse into the past and its possibility for changing the future.

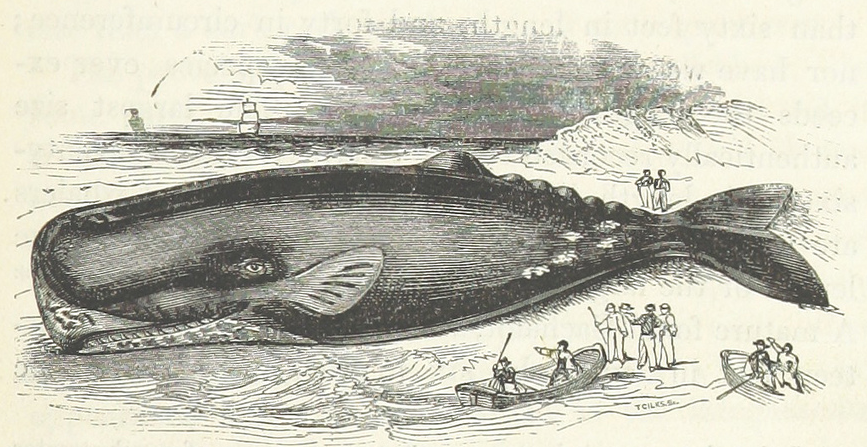

Moby Dick; Or The Whale

via Gutenberg.org

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island. He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).