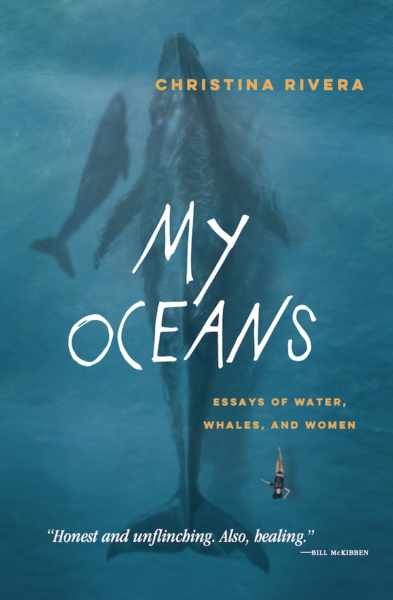

Christina Rivera is an author from Colorado whose girlhood was bordered by coastlines of the Pacific Ocean. Her debut book, MY OCEANS was longlisted for the Graywolf Press Prize, a finalist for the Siskiyou Prize for New Environmental Literature, and publishes this month with Curbstone Books, an imprint of Northwestern University Press.

Here’s a recent Q&A with her regarding her new book…

What inspired you to connect human motherhood to the motherhood of marine animals? What are some of the similarities and connections among humans and these nonhuman species?

Motherhood was my portal to my animalness. Pregnancy was the wildest experience in the truest sense of the word “wild” as “living in a state of nature, not tame or domesticated.”

I traveled around the world for a decade before I got pregnant, but no place I adventured was either as wondrous or desolate as the years I lived in various states of four pregnancies (of which two failed and sent me to some foreign lands of depression). If pregnancy was a pilgrimage that made me question the borders of my being, the physical act of birth was the Grand Canyon of my deconstruction of self. I was suddenly multiple people and yet also newly connected to every mothering body on the planet with an experience of caring for a split self.

I wrote of these four journeys of pregnancy in the essay “Four Circles,” which was the first finished essay in my debut book titled, My Oceans. The essay itself uses a re-arranged timeline because pregnancy shattered my understanding of time, too. So motherhood broke me into pieces and when I resurfaced, I saw new patterns—interconnections I felt newly compelled to explore with words.

Mothering whales feed their babies with milk that “lets down” from mammary glands. That fact, no matter how many times I write about it, still breaks my brain. Does the young mother whale know what’s happening when her new infant first nuzzles her body and a novel function of her body kicks into sudden gear? I was so humbled by the secret animalness of my body that “let down” in my process of becoming a mother. Before my babies, I saw the whale as a mythic-like creature of 50,000+ pounds swimming in a foreign water world. I didn’t see myself in her. But now I can feel into her. When my babies cried, my breast milk dropped it felt like ice breaking in my chest. That the whale and I share in theses mammalian functions and instincts makes me feel directly connected to the 80% of my DNA that I share with the whale. Did you know whale poachers used to first target and harpoon the babies of mother whales? They’d aim for the calves, kill and then drag the infant bodies from the whaling vessel to lure the mothers into the crosshairs of their harpooners. When I first read of that tactic, I wanted to throw up. And that nauseous share of emotional pain makes me feel more connected to my mammalian-ness, than my humanness.

What is it that has drawn you, time and again, to your explorations of the oceans and their magnificent creatures?

I recently went whale watching with my children. Our boat came upon a pod of Humpbacks. As the whales breached, my son jumped up and down so many times he fell to his knees. On his knees, he kept hooting and his body trembled. My daughter crawled into my arms and cried. But it wasn’t the cry of fear so much as the leaking of an emotion she could not contain. She held my arms across her body as if she might just float off into the sky otherwise.

When I volunteered in Costa Rica to help relocate Leatherback Turtle nests safely away from egg poachers, the marine biologists instructed us to scan the sand for turtle tracks that looked, “like tire tracks from a Jeep.” The arms of the Manta Ray that flew overhead in my essay, “Two Breaths,” spanned about 19 feet in width. So, the sheer size of these marine creatures can steal anyone’s breath away! But I think it’s their otherworldliness that cracks our understanding of what’s possible, and what’s not, in half. And I’m always writing into that crack. Because I want to live there.

Last September, I did a reading at a literary festival near the San Juan islands. While there, I visited some cliffs where I knew the local pod of Orcas often swim by. On the cliffs, I was surrounded by other onlookers, perched with binoculars and cameras, waiting. Regulars. People who listened to the hydrophones in their kitchens and checked the social forums for news of the pods in the same way my mom checks the news for updates on the weather. On those cliffs, when a fin did finally pop up, the crowd gasped like they were all tourists. That’s how I want to live. Like a “regular” moving through my daily with the eyes of a tourist. You can hear the Orca’s breath, too, when it surfaces. It also gasps! It might be my favorite sound on the planet. It feels sublime, in the truest sense of the word, “impressive to the spirit.”

These encounters feel like moments of transcendence, right here on Earth, in my plain old (and faltering) human body. I’m a student of Thích Nhất Hạnh’s teachings, and he called the feeling of deep interconnection, “interbeing.” When the whale breaches, and when my heart breaches watching the whale, I get to touch that feeling of interbeing for a brief, buzzing, second. Writing about that buzz allows me to revisit those seconds, to set up camp for a while, and to live longer in them.

Your essays portray such emotions as grief and helplessness — but also resilience and hope. What makes you feel optimistic in this era of climate anxiety and mass extinction?

What makes me feel alive is a fight worth fighting. And a circle of community willing to die in the process of protecting what they love. I love people who hurt when the earth hurts. I love the people who cry when the culture of control appears to beat out the culture of caring. I love the people who choose to fight for what they love despite the odds. What we lack in number, we can make up in heart and spirit. And we don’t have to be overwhelmed. We can pick just one thing. Be it sea turtles, or rivers, or neuro divergency, or unhomed people, or Monarch butterflies, or reproductive rights, or whatever. I’m surrounded by people who care and make humanity worth bearing. If someone doesn’t know where their people are, I always say just pick something you love. Begin to fight to protect and care for that one thing, and you’ll soon find where those people collect. And who wouldn’t want to be surrounded by lovers of Monarch butterflies? That’s a group I need to get in with next.

What environmental books and/or authors have most inspired you?

Oh, there are so many. Rachel Carson. Linda Hogan. Eva Saulitis. Robin Wall Kimmerer, of course. Ursula K. Le Guin. Terry Tempest Williams. All of my Carl Safina’s books are heavily underlined. Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés Réyes is a treasured guest from another world. Dr. Bayo Akomolafe’s work on post-activism and Francis Weller’s words on themes of grief and gratitude, too, have been formative to all my thinking and writing.

What’s your next writing project?

I have two books currently talking to me. One is a novel of which I have one full, bad, draft. I wrote it partly out of spite while My Oceans was on submission just to prove I knew the difference between when a narrative book, and a fragmented book, was talking to me. But it’s a third book that is currently waking me up in the night with its chatter. Now that I’m writing fresh pages into that book, I can see it’s a project that’s been trying to find a way out of me since I was twenty-three and first walked one of the Caminos de Santiago across Spain. I’ve kept the characters in that story bottled up so long, my dialogues are now falling over themselves when I put pen to paper. The characters are so excited to finally talk to each other. And that’s all fun—the very best stage of writing a book in my opinion. But now that I know all the other things needed to get a book from sloppy first sentences to print, well . . . actually, let’s not go there. Let’s stay on the page—in awe of what breaches.

Christina’s essays have won a Pushcart Prize, the John Burroughs Nature Essay Award, and appeared in Orion, The Kenyon Review, and Terrain.org, among other places. An adapted excerpt from My Oceans was recently published at The Cut if you’d like to read a sample essay. You can learn more about Christina and My Oceans at www.christinarivera.com.

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island. He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).