Nearly 30 years ago, the first genetically modified (GM) seed produced a tomato known as the Flavr Savr. The tomato was engineered for longer shelf life which was where it spent most of its time. Consumers didn’t like the way it tasted and it soon went the way of history.

But that didn’t stop Monsanto from seeing the massive potential for creating GM seeds that could be patented and packaged with matching pesticides. Monsanto bought the company that created the Flavr Savr and soon became the leader in GM crops, followed by Dow and Syngenta, which author Liza Grandia in Kernels of Resistance: Maize, Food Sovereignty, and Collective Power refer to as the “the evil stepsisters.”

Evil, as readers of this book will discover, is an understatement.

While the United States (mostly) capitulated to GM crops (more than 80% of US crops are now GM) a number of other countries put up a fight, such as Guatemala and Mexico.

Guatemala is a small country home to countless varieties of maize (corn) that farmers have nurtured, cross-bred, saved and traded for thousands of years. Maize is the foundation of the food system, culture and economy. But Monsanto wanted in. Though the country had initially banned the planting of GM, in 2014, Monsanto (backed by heavily funded US trade interests) pressured Guatemala to lift its ban.

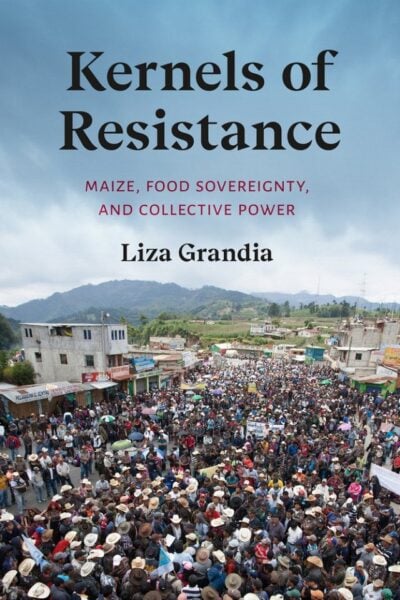

Yet Monsanto and the government were not expecting the largest waves of protests in the history of Guatemala, coordinated in part by the international, peasant-led Via Campesina movement. The law was quickly reinstated. But the battle was far from over.

Mexico, which also bans GM seeds but not the importation of GM crops, is now in the crosshairs of an American government that views it in violation of its most recent trade pact (expect to read much about this in the months and years ahead).

This is much more than a book about protests and politics. It’s about the evolution of corn, organic agriculture and the origins of pesticides. It’s about the misguided belief that mono crops and chemicals are essential to feeding a growing world. Agtech companies have convinced the world that they are innovating whereby individual farmers are not. Grandia introduces us to farmers who have adapted maize to nearly every elevation and ecosystem, simply through selective crossbreeding and patience (and no toxic chemicals). What’s more innovative than that?

While this book is largely about battles taking place south of the US border, there is plenty that Americans can do to help independent farmers. Grandia writes:

Because 80 percent of US grains go into animal feed, the single most impactful act any “eater” can do for climate change or global hunger is to consumer less meat. The average steer requires 130 gallons (3 barrels) of oil over its lifetime. A US family can offset its average annual car travel (2,938 miles) simply by cutting its meat consumption in half … Happily, one can eat least meat without resorting to gruel or the generic Esperanto cuisine of “hippie food.” Mesoamerica boats a plant-based cuisine that the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) honored in 2010 as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The complexity of the region’s sauces, beverages and versatile staples are mirrored in the beauty of its polycropped milpa system.

In other words, when we eat less meat we deprive corporations from the growing demand for GM corn and we take pressure off of smaller farmers around the globe who are simply trying to feed themselves and their communities.

While there is much to lament in this book — the chemicals we have willingly allowed to enter our lands and our bodies — there is also much to be optimistic about. Such as the collective power of those who refuse to sit quietly. And there is room for optimsm even here in the US. I live in Jackson County, Oregon, one of a handful of counties in the US to have successfully banned the planting of GM crops.

Grandia argues that we’re gradually leaving behind the corporate food regime for a regime of climate resilience led by indigenous knowledge, small farms and organic agriculture:

I have also long pondered what in today’s world would be an equivalent symbolic action against corporate power to Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha (nonviolent truth-force) against the British Empire. … By encouraging people to grow their own gardens, the food movement similarly gives people a method and means to remove a piece of their lives from corporate markets and build community. The home and community gardening movement costs across the political spectrum and shows how the personal can be political.

Ultimately, this is hopeful book. True, the battles are far from over yet farmers around the world who were sold on the many merits of GM seeds are realizing that they have been lied to. That they are killing their soil with chemicals. That the seeds don’t work as well as they once did. And that insects are becoming immune to all those pesticides. In other words, farmers are learning to listen to their ancestors and, perhaps, to themselves.

There is much talking of “resistance” as of late. Read this book to learn how to resist the corporations who would rather you not know what you are eating. And read this book to appreciate the miracle that is maize and its many heroic defenders.

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island. He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).