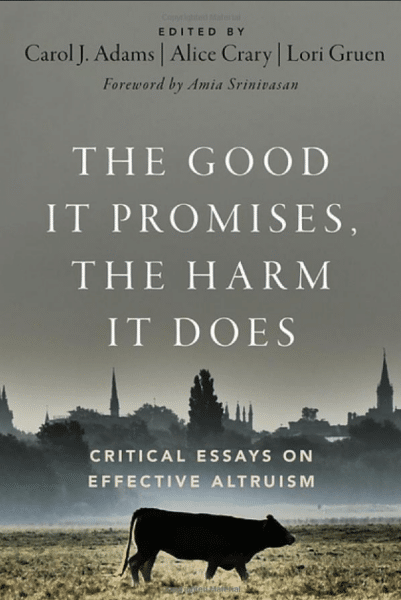

The term “Effective Altruism” has been buzzy for a while now and has attracted well-known followers and promoters — and because of this, the movement is generally associated with doing good. However, The Good It Promises, The Harm It Does: Critical Essays on Effective Altruism asks, “What if Effective Altruism, whatever the intentions of its leaders and followers, systematically harmed those it promised to help, eroding democratic decision-making, creating perverse incentives, and reinforcing the very structures that produce the suffering it purports to target?” The individual essays collected here answer these questions, and many more.

As the book describes, Effective Altruism is “a philosophy of charitable giving that claims to guide adherents in doing ‘the most good’ per dollar donated or time spent.” Yet the book’s editors — feminist and activist Carol J. Adams and philosophy professors Alice Crary and Lori Gruen — describe a 2020 animal rights conference in which both scholars and activists shared the ways in which EA was in fact harming the work of animal protection. Among the outcomes of EA policies were sanctuaries losing funding because “caring for animals and feeding them in sanctuaries were ‘ineffective’ approaches to animal advocacy”; community activists in marginalized communities losing funding because their work wasn’t deemed effective; and food justice advocates losing funds for local projects in favor of large-scale food production or industry reforms — among other issues. These seventeen essays address effective altruism and its effects on community and grassroots activism, animal protection, feminist and LGBTQ advocacy, and more.

In her essay “How Effective Altruism Fails Community-Based Activism,” Brenda Sanders — whose work through the Afro-Vegan Society and Vegan SoulFest, among others, has reached tens of thousands of individuals through workshops, film screenings, and festivals — writes, after learning of a prominent donor refusing to fund her work, “judging the effectiveness of my work based on a ‘return on investment’ model was, at its core, based on a white-centric view of activism.” She argues that on-the-ground activism is the only way to effectively reach the low-income communities of color that the mainstream animal rights movement “glaringly disregard.” She argues for the need for trust, relatability, and cultural relevance when it comes to animal rights activism, and that “refusing to support work being done by a Black activist in Black communities is upholding white supremacist ideas about which communities are worthy of support and which ones aren’t. In other words, it’s racist, plain and simple.”

Likewise, Christopher Sebastian argues in his essay “Anti-Blackness and the Effective Altruist,” that the “inability to recognize systemic racism, or the unwillingness to confront it, creates a space in which EA supports a racist system.” Compiling data from EA sources, he notes that “EA is mind-blowingly white,” which translates to approaches, strategies, and viewpoints that remain within this population to the exclusion of others: “Lack of Black representation means that EA conversations about activism, practice, and theory occur uninformed by Black experience and insights.” EA can hardly do the “most good, most effectively,” Sebastian points out, if it is limited by such a profound lack of diversity within its organizations. This essay offers myriad examples of systemic racism within the animal rights movement, concluding that by “diminishing the role that race plays, Effective Altruists run interference for the class of monied people who drive inequality by producing racist and anti-animal outcomes…Far from changing the world, these groups work together to keep the world mostly as it is.”

Not all essays are as critical of EA as others, though all take EA to task for its single-minded goals at the expense of other worthy projects. The five authors of “Animal Advocacy’s Stockholm Syndrome” note that success takes not one approach or another but myriad paths forward: “we must hold together, always, the next step and the final goal. We must focus on reducing the suffering of chickens and sea animals, for example, and we must simultaneously focus on ending the entire exploitative factory farm system.”

EA’s support of cultured meat — with its flood of financing, Matthew C. Halterman suggests in his essay “Diversifying Effective Altruism’s Long Shots in Animal Advocacy” that the effort could be more accurately called “Venture Altruism” — is one example EA’s support of an endeavor with the potential to save far more animal lives than, say, a farm sanctuary. Yet the essays “The Empty Promises of Cultured Meat” and “How ‘Alternative Proteins’ Create a Private Solution to a Public Problem” both detail the harm in EA’s commitment to cultured meat over other animal rights and environmental issues.

And, as David L. Clough points out in his essay, “A Christian Critique of the Effective Altruism Approach to Animal Philanthropy,” a visit to a farm sanctuary can be life changing to those who see farmed animals living out their natural lives in a safe environment. As Clough writes, “it is not possible to quantify what the impact of that transformative encounter might be.”

Kathy Stevens offers firsthand evidence of this transformative effect in her essay “Our Partners, The Animals: Reflections from a Farmed Animal Sanctuary,” pointing out that EA ignores the fact that “sanctuaries are vegan-makers.” And Krista Hidderma’s “The Power of Love to Tranform Animal Lives: The Deception of Animal Quantification,” with its story about Esther the Wonder Pig, further highlights that not all giving is quantifiable — far from it. “What EA thinkers continually fail to realize is that emotions are why people stop eating meat…and why people stop going to Sea World, and why people don’t buy fur coats.”

As patrice jones, cofounder of VINE Sanctuary, writes in “Queer Eye on the EA Guys,” EA’s focus solely on the big picture of the future does not alleviate harm in the present: “EA encourages a kind of calculating dispassion that can lead to callousness. When EA adherents insist that the suffering of actual animals must be ignored in order to focus on reducing as much future suffering as possible, something has gone badly wrong with the reckoning.”

In all, these collected essays offer passionate, well researched, and thoughtful arguments for recognizing the harm that can come from narrowly focused EA endeavors. While EA has, as Halterman writes, “a snappy brand and a compelling project,” its leaders need to take a closer look at its actual effectiveness, in particular how EA’s homogeneity has led to the exclusion of so many communities and causes.

Common themes appear in these collected essays, but the book never feels redundant; the myriad data and personal experiences brought to each essay by their contributors reinforces the ideas of why EA needs to be examined and held accountable — especially the reminders that what motivates people to give or change is not always based on what is considered most efficient. As these essays point out, efficiency isn’t — and perhaps shouldn’t be — the driving force for philanthropy. As David L. Clough writes, “It is unhelpful to think that you are searching for the single most effective way your money can be used. Instead, you are looking for a good way to support a project that aligns with your priorities, is well-run, and looks like it has a good chance of achieving its goals.” And patrice jones similarly writes that the best activism means “looking for the best match between what you have to give and the many different things that need to be done.”

Midge Raymond is a co-founder of Ashland Creek Press. She is the author of the novels Floreana and My Last Continent, the award-winning short story collection Forgetting English, and, with John Yunker, the suspense novel Devils Island.