We want to believe that cows live happy lives. From our childhoods of Old MacDonald and his farm, field trips and cartoons and stuffed animals, we are raised to believe they are happy. The dairy industry tells us they are happy. The advertisements we see on TV reinforce the illusion. But it is only an illusion and more of us are awakening to the cruel reality of the world we have created for them. A world in which animals — cows, chickens, goats, sheep, and so many other species — are viewed and treated as little more than their component parts.

Why should a cow not receive the same degree of love and protection as the cat or dog we share our homes with?

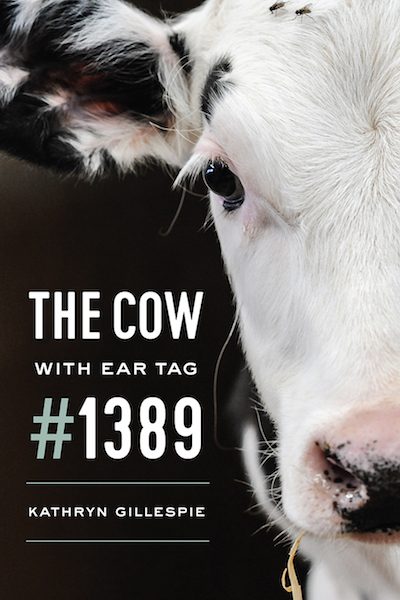

This is a question in desperate need of an obvious answer. So I’m always happy to see more authors and publishers posing this question. Like this book by Kathryn Gillespie, published by the University of Chicago Press.

In The Cow with Ear Tag #1389 Gillespie takes us on a necessarily uncomfortable journey through America’s dairy industry. The core illusion built around the dairy industry is that cows somehow want to share their milk with us. And that they want to be milked. But the truth is, the milk is there for a very specific reason, one that is stolen from them every year. Each year, dairy cows are artificially inseminated and separated from their newborn calves within minutes after birth. A mother cow may bellow for weeks, calling out to a child that has been taken from her. Of course we can imagine the terror of this because we can imagine ourselves losing a loved one. And yet this is how milk is made. Cows don’t want to give their milk away. They create it for calves who are most often sent straight into veal crates, which the industry now euphemistically refers to as “hutches.” And the fact that the dairy industry is very much intertwined with the veal industry has long been the industry’s dirty little secret.

Gillespie is not the first person to analyze animal agriculture, but she provides an honest and human element to the journey that I found deeply moving. Her candor throughout her visits to farms and auction houses had me squirming in my seat as she watched those poor animals being pushed and prodded along. And it was not surprising but sad that nearly every dairy farm she approached for her research turned her away under the sad excuse of “biosecurity.” This is an industry that thrives on ignorance. On illusion.

But this book is not all pain and misery. There are inspiring moments amidst the stories of those who have founded animal sanctuaries, like Animal Place and Pigs Peace. Gillespie takes us along with her, where we can get a sense for what it’s like to care for an animal after it has suffered so much. As the founder of Pigs Peace noted, she had difficultly finding vets who understood how to care for aging pigs because in our world pigs aren’t allows to age. They all die young, as do cows and chickens. Those few chickens who do make it to sanctuaries have great difficulty simply standing upright because they were bred to get large quickly, so large that they can barely support their bodies.

Gillespie notes that there are 9.3 million dairy cows in the US that are used for their milk until they are “spent” after about three years and then sent to slaughter, to the tune of roughly 3 million cows per year. As Carol Adams writes in The Sexual Politics of Meat, “Female animals are doubly exploited: both when they are alive and then when they are dead.”

This is world I was raised into. A world in which I assumed we needed meat to survive, that violence to animals was necessary. I know now it is not necessary. That humans don’t need meat to survive and that we have never needed milk from a cow or a goat.

Gillespie is not out to belittle those who work in the industry — she is empathetic to the worlds they live in as well, and the emotional toll this work ultimately exacts on them. They are part of a system, a system that supplies a demand based on illusion, based on a tradition that so many of us except without question. Gillespie travels to a trade conference and notes how intertwined the dairy industry is with notions of family and patriotism and what it means to be an American. And it is these ideas that make it so difficult for people to give up milk and cheese and ice cream (even though they don’t have to give up any of it — vegan alternatives are far tastier and healthier).

This book is a valuable addition to a growing canon of literature that challenges our understanding of “normal” and that will, hopefully, as more people become aware of the horror, lead to positive changes for animals. It’s simple enough to start, really. You just stop eating meat and go from there. The Cow with Ear Tag 1389 is doing its part to opens hearts and minds.

John is co-author, with Midge Raymond, of the Tasmanian mystery Devils Island. He is also author of the novels The Tourist Trail and Where Oceans Hide Their Dead. Co-founder of Ashland Creek Press and editor of Writing for Animals (also now a writing program).