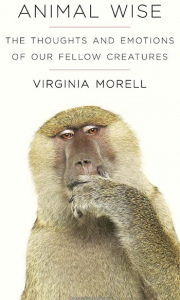

It’s been wonderful to see new books about animal minds and emotions, from Barbara King’s How Animals Grieve to Virginia Morell’s Animal Wise: The Thoughts and Emotions of Our Fellow Creatures (Crown, 2013), which offers a fascinating look at the emotional lives of a wide range of animals.

Morell writes that it was in part due to her dog Quincie that she began to think about writing Animal Wise—when Quincie created her own game to play, Morell realized the extent to which animals have imaginations. As a science writer, she’s reported on animal studies before, including the work of Jane Goodall, with whom she witnessed chimpanzees being as clever, cunning, and resourceful as humans. In one example, a chimpanzee named Beethoven ate his fill of bananas without sharing with a younger female, Dilly; when Dilly was offered a banana later, she cleverly waited until Beethoven was asleep, then gulped it down as he snored away. Morell recalls how Goodall noted that she couldn’t record this behavior in a science journal because “everyone will say, ‘Oh, Jane, how silly of you. That’s anthropomorphizing.’”

Morell’s book, while filled with its share of anecdotes, aims also to show through science the ways in which animals think and feel—and the stories and research presented in the book leave no room for doubt. Animal Wise features the usual friendly suspects—dolphins, elephants, birds—whose gifts many readers may already know; yet one of the great aspects of this book is learning about the animals we think about more rarely as being emotional and/or intelligent: for example, fish, ants, and rats.

As Morell mentions in her introduction, our world is largely human-centric, and she hopes that Animal Wise helps us rethink this view: “I don’t know if knowing more about animal minds will help improve the lives of humans, although this is usually the rationale scientists, particularly neuroscientists, must use to justify their research. But knowing more about the minds and emotions of other animals may help us do a better job of sharing the earth with our fellow creatures and may even open our minds to new ways of thinking about and perceiving our world.”

Among the most fascinating sections of the books in the first chapter, “The Ant Teachers.” In this chapter, we learn that ants teach one another—and we’re shown this world by Nigel Franks, University of Bristol in England, who calls the ants he works with “people.” When Morell corrects him, telling him, “They are ants,” he replies: “ ‘I don’t like thinking of them as machines as most people do. Most people think ants are stupid, to, but they’re not. They have very sophisticated behaviors…and they’re very generous in giving up their secrets.”

To tell his ants apart, Franks paints dots upon their backs, and thus he can see them as individuals and watch them solve problems, teach one another, and build and rebuild their homes. Morell also points out that this research fits in with other insect studies that show that insects from wasps to crickets to honeybees have cognitive abilities that most humans cannot imagine. “What is true for computers also holds for animals,” she writes: “a big machine isn’t necessarily a better one, nor is a big brain a good measure of one’s ability to think or solve problems.”

Also fun and surprising is to learn about the emotional lives of fish. In the German lab of Stefan Schuster, we witness archerfish lining up in their tanks as if awaiting researchers, and shooting them in the eyes with water (normally the way they hunt their prey, mostly insects). This act is something one of the researchers, Thomas Schlegel, suggests they might be doing for fun, to enjoy the reactions. “ ‘Sometimes I get the feeling they’re watching me,’ he said. ‘And when I turn to look at them, there they are, lined up like this, waiting like dogs for their humans. They try to catch their attention.’” The archerfish studies focus on the way the fish learn to hunt, with amazing speed and accuracy—Schuster’s studies show that they make precise calculations regarding distance and force, and that the younger fish learn from the more experienced ones: “ ‘That means it is cognitive; it is not because of some built-in, hardwired neuronal machinery.’”

One of the interesting questions about the implications of this book for how we treat animals comes up in the fish chapter, when Penn State fish biologist Victoria Braithwaite brings up the difference between pain and suffering. It is clear that, with pain receptors on their heads (trout have twenty-two of them), fish do feel pain—but Braithwaite notes that in science, this is different from suffering. She poses the question: “ ‘Do fish suffer when they sense that pain? Suffering is the cognitive side of pain.’”

Braithwaite’s research indicates that fish, which have an amygdala (a part of the brain that processes basic emotions), do suffer. When given lip injections of pain-causing substances, trout react by rocking back and forth, by rubbing their lips on the sides of the tank, and showing other signs of having suffered from pain. This is information that anyone who eats fish might consider before taking another bite.

Many readers may be surprised to learn that one of our least popular animals, the rat, is also among the most playful and affectionate. In Jaak Panksepp’s Washington State University lab, rats play and laugh, and are tickled by researchers in order to show their capacity for joy. Other chapters cover territory many animal lovers may already know—Alex the African gray parrot, who learned not only words but their meanings and how to communicate; elephants, who memorize the voices of other elephants and who caress the bones of the dead; chimpanzees, who are so humanlike; and dolphins, who exhibit signs of self-awareness—but they’re important nonetheless, if nothing else to remind humans that the way they are treated (forced into captivity, for example, or used for medical research) needs to be reevaluated based on what we know about their emotional lives.

Animal Wise brings up a lot of important questions but offers few calls to action; I’d have loved to see connections made between how animals think and feel and suffer, and how we treat them (usually not well). This book shows so clearly that we need to do better, from animal testing to using animals for food, and my hope is that readers will make these connections for themselves.

Morell poses a question at the end of her chapter on fish —“even if an animal could talk, would we listen?”—and unfortunately, the implication here is that we would not. This Q&A with the author offers some insights into Morell’s personal thoughts on what she learned in the writing of this book and the ways in which it has, and hasn’t, changed her own view on animals.

I would recommend Animal Wise for anyone who cares about animals, not only for the wonders it reveals but for the chance it offers to make a difference in their lives. As Morell writes: “What do the minds of animals tell us about ourselves? That, like us, they think and feel and experience the world. That they have moments of anger, and sorrow, and love. Their animal minds tell us that they are our kin. Now that we know this, will our relationship with them change?”

Midge Raymond is a co-founder of Ashland Creek Press. She is the author of the novels Floreana and My Last Continent, the award-winning short story collection Forgetting English, and, with John Yunker, the suspense novel Devils Island.