Terra Firma Books, Trinity University Press, 2025

This fine collection of essays by Simmons Buntin, Satellite: Essays of Fatherhood and Home, Near and Far, leads with lizards. “They are tidy, amiable housemates that give us good reason to avoid pesticides.” The landscape is the American Southwest, and the over-arching question is how to appreciate and gently co-exist with nature and children, even while parenting in a neighborhood of javelinas and rattlesnakes. In “The Sum of All Species,” Buntin’s ten-year old daughter, Ann-Elise, catches a whiptail lizard. She and her sister have always collected small critters, kept for careful observation in terrariums and jars before being released back to the prickly wilds of the backyard. But Ann-Elise is determined to keep this lizard as a pet, and Buntin relents after he is assured that she has done the extensive research required to meet the lizard’s needs. He believes the inter-species relationship will help “establish her sense of connection to the natural world.” And there-in lies the beauty of the book, as over the years he invites his two girls to view the world as a fellowship of beings. Quoting Aldo Leopold, he writes, “We abuse land because we regard it a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

In all the essays, Buntin ponders humanity’s place in this community. “Not the multiplication of our own species, but the survival of all species.” In “Stopover,” he and his other daughter, Juliet, drive 1200 miles to Nebraska to witness the sandhill cranes (which brought back fond memories of Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, perhaps one of the first adult novels I’d ever read that put humans and another species on equal footing) and are lucky enough to spot a whooping crane, one of the rarest birds in North America. Their population once fell to sixteen due to habitat loss; today there are maybe six hundred thanks to extensive human intervention. In “Songbird,” after the windshield death of a robin, he blames the lure of his new i-pod that dampened his attention to the world around him as he drove through the hills of Vermont. This leads him to wonder about electronic distraction and loneliness, and that wonder leads him to action. On the advice of his friend David Rothenberg, the author of books on insect and whale song, Buntin goes hiking while listening to rock & roll. Yes, he feels disconnected from his surroundings, but then his walk begins to feel somewhat cinematic, ending in an unexpected place after multiple twists and turns of his internal experience.

Buntin’s topics are wide-ranging as he and his family explore the earth and the skies, visit relatives, and go to the occasional brew pub. In “The Biter on Tap,” his paean to Buffalo Gold from the now-defunct Walnut Brewery in Boulder was so effusive—“a full pint with a resonant caramel base and thick, foamy head that quivered slightly at the edge of the glass but did not run over, nor faltered in its slow retreat into the smooth body of the ale”— that I regretted never going there, and I don’t even like beer. It also serves as a jumping-off point for beer-themed history. Fun fact: The Mayflower stopped at Plymouth, Massachusetts instead of continuing to its Virginia destination because the beer ran out. More history is to be found in “The Days of the Dead,” a piece about his family’s extreme Halloween traditions. Another fun fact: In the 7th century, the Catholic Church co-opted a pagan holiday by calling it All Saints Day, or Alholowmesse in Middle English, which morphed into the word we know today. Buntin also considers how heritage and tradition are maintained in America, a land of immigrants. “The Castaway” is a visit to El Tiradito, the nation’s only Catholic shrine dedicated to a sinner instead of a saint. You will have to read that essay to find out the convoluted history of that, but it sets Buntin to ruminating about what makes a place sacred. He comes to the conclusion that “community is, after all, what we make it, and the making itself is the sacred.” In another essay, “The Bells of San Borja,” which looks at a community in the aftermath of a child’s sudden death, the sacred grows from intense sadness and pain, “the sublime suddenness of a small, unexpected discovery—a split geode on the trail’s edge, a small bell glittering in a tree.”

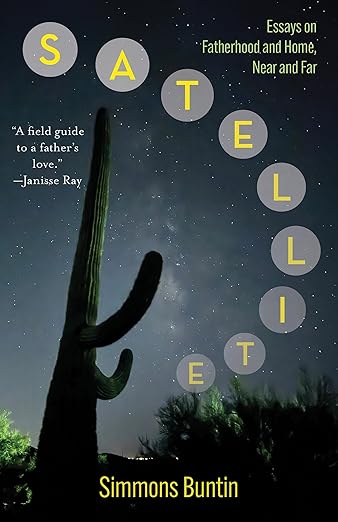

The girls grow older over the course of the book. In “After,” an essay that links the recovery of Mount Saint Helens with Ann-Elise’s recovery from a horrific accident, the seventeen-year-old pushes back against parental ties as Buntin pushes food on her. “I was still her annoyingly concerned father, the satellite whose orbit was suddenly too tight.” Satellite proves to be an apt title for this book, since a satellite is tethered by gravity to another body to keep the community of planets in order. We revolve around one another.

JoeAnn Hart writes about the pervasive and widespread effects of the climate crisis on the natural world and the human psyche. Her most recent book, Arroyo Circle, a story of reclamation in a time of loss, was released by Green Writers Press in 2024. Her other books include the prize-winning environmental and animal fiction collection Highwire Act & Other Tales of Survival, the crime memoir Stamford ’76: A True Story of Murder, Corruption, Race, and Feminism in the 1970s, as well as Float, a dark comedy about plastics in the ocean published by Ashland Creek Press, and Addled, a social satire. She is a regular reviewer of climate and animal fiction at EcoLit Books.